Constructivist Art Activity: Designing an Online High School Art Class with The Studio Habits of Mind

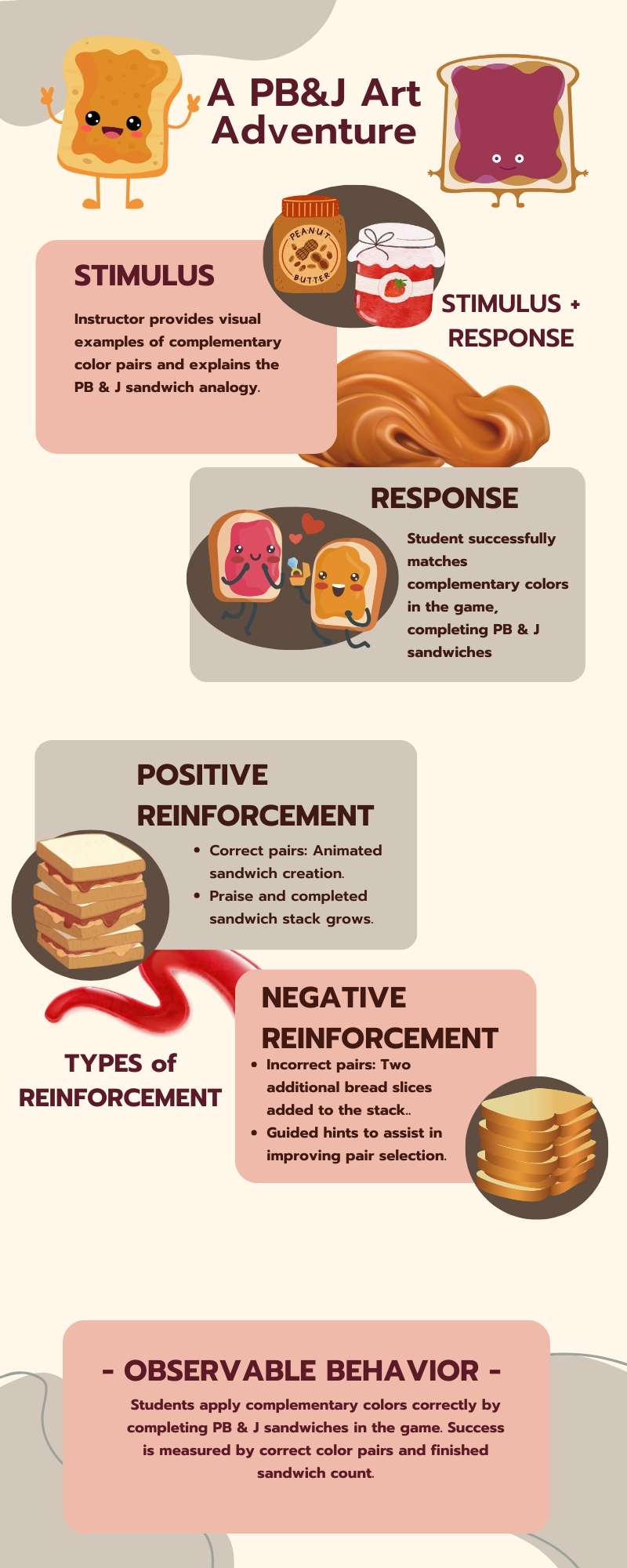

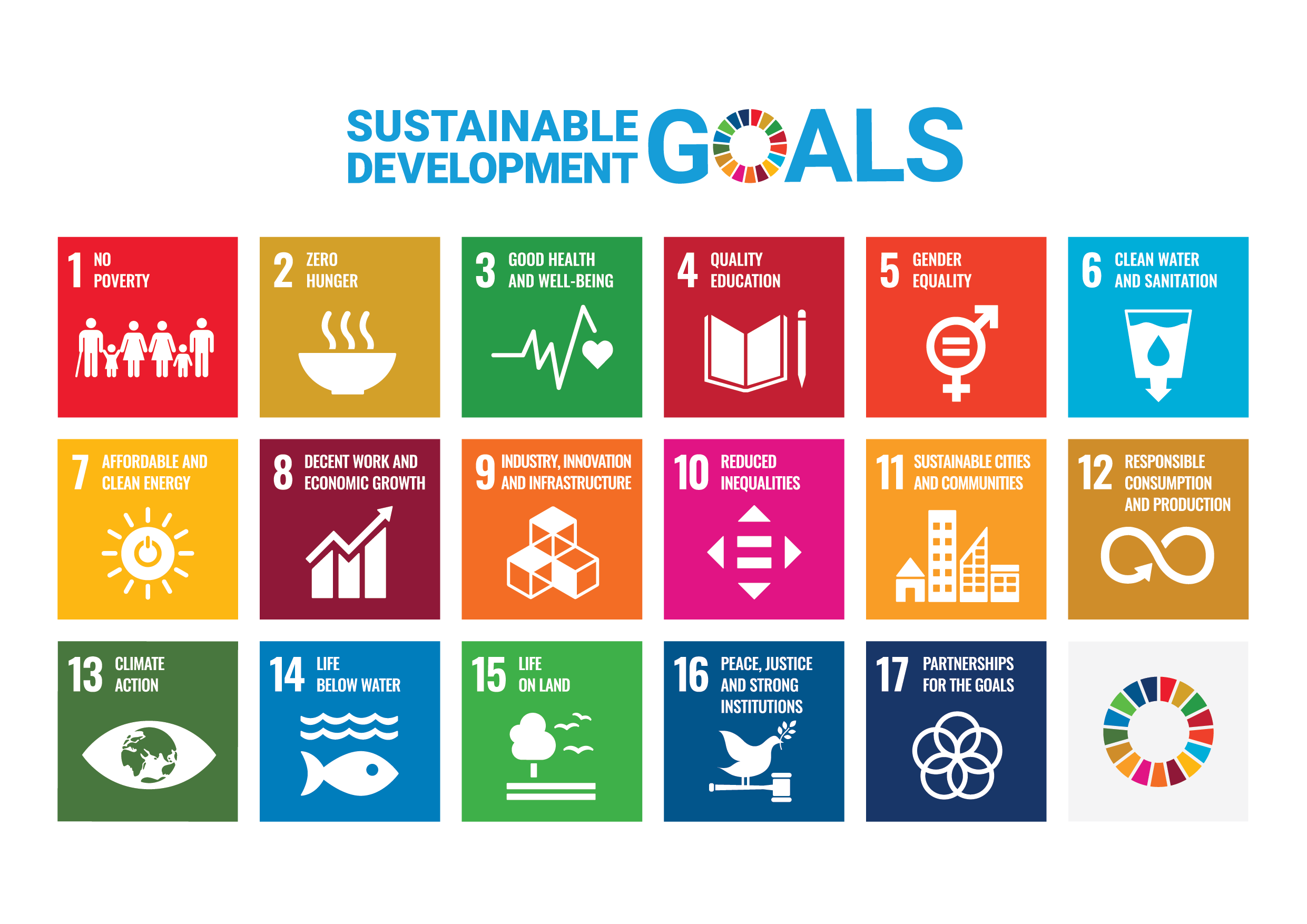

Introduction to Studio Habits of Mind: The Studio Habits of Mind (SHoM), developed by Harvard University’s Project Zero, provide a framework for fostering creativity, problem-solving, and critical thinking in visual arts education. These eight habits—including Develop Craft, Observe, Reflect, Express, and Stretch & Explore—are designed to help students engage deeply with the artistic process and connect their work to broader cultural and social contexts. Each habit emphasizes the active and reflective construction of knowledge, aligning closely with constructivist learning theories.

In my opinion, I feel that integrating the SHoM into this activity is an effective strategy for exploring Constructivist Learning approaches as the SHoM promote active learning where students explore, experiment, and reflect on their artistic decisions. Through situated learning, students encounter real-world challenges, applying artistic skills and perspectives to create meaningful projects. Collaborative elements support social interaction, further reinforcing the co-construction of knowledge.

The Studio Habits of Mind

Project Zero. (2003). Studio thinking: The real benefits of visual arts education. Retrieved from https://pz.harvard.edu/resources/eight-habits-of-mind

Scenario: Community Narratives: Visual Voices

In this scenario, students in an online high school art class embark on a project called “Visual Storytelling Through Community Narratives.” The objective is for students to create a series of “living portraits of the community” that put visual form to the voices and stories shared by community members. Throughout the project, students will apply the Studio Habits of Mind (SHoM), including Develop Craft, Observe, Express, and Stretch & Explore.

To begin the project, students will explore a “community seed bank” — a collection of audio recordings where various community members share stories and themes that have shaped their community’s development. Students listen to these stories, using a worksheet to organize and reflect on familiar narratives as well as those that offer new perspectives. This approach emphasizes active learning, where learners engage with authentic materials to build knowledge. By connecting with real-world contexts through situated learning, students are prompted to reflect and engage in social interaction to co-construct new understandings, aligning with key principles of constructivist theory. This approach is rooted in constructivist learning theories, which emphasize the active construction of knowledge through engagement with meaningful, real-world contexts. By connecting with authentic community experiences, students are prompted to question, reflect, and build new understandings through exploration and social interaction. This initial exploration serves as a starting point for their research, allowing students to identify themes of personal relevance or curiosity. These portraits are not literal representations of people but can take any artistic form that the students feel best conveys the narratives they have explored and wish to share. From there, they interact with community members to gather further insights and use various artistic techniques to create a visual narrative. This process reinforces social interaction as students actively engage with diverse perspectives, fostering deeper understanding. Towards the end of the project, students present their portraits to the community members during the virtual art exhibition, allowing for reflection, feedback, and collaborative assessment. This final dialogue emphasizes the reciprocal nature of learning, as both students and community members share and interpret the visual stories together. The class will conclude with a virtual art exhibition where students present their community portraits and discuss how their artwork captures and interprets the stories and themes they explored. This final presentation encourages reflection on their artistic choices and their role as storytellers within the community.

Identified ZPD Skills and Studio Habits of Mind

Based on this scenario, the following skills lie within the students’ Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD):

- Developing Craft (SHoM) and Technical Skill Development (ZPD Skill):

- Learning to use new artistic tools and materials to convey visual narratives.

- This involves guidance on mastering techniques like digital illustration or mixed media.

- Observation (SHoM) and Research (ZPD Skill):

- Enhancing the ability to observe their surroundings deeply and gather meaningful insights about their community.

- With teacher or peer support, students learn to document visual and contextual details effectively.

- Express (SHoM) and Articulation of Ideas (ZPD Skill):

- Developing the ability to clearly express the story behind their artwork through artist statements and discussions.

- Learners need scaffolding to organize their ideas and articulate connections between their research and artistic choices.

Scaffolding Strategy for Conceptual Development

To support the development of these ZPD skills, the instructional designer will implement a scaffolding strategy that includes structured guidance to gradually develop mastery:

- Tiered Conceptual Development:

- At the most basic level, students begin by creating a literal visual representation of what is happening in the story shared by the community member. This step familiarizes them with the basic narrative elements.

- In the next tier, students are encouraged to create an image that visualizes how the story impacts or contributes to the community’s development. This includes integrating symbolic elements that convey emotions and underlying themes.

- At the advanced tier, students consider how the story connects to broader aspects of the community, incorporating multiple narratives or motifs that reflect interwoven experiences and identities.

- Throughout this process, guided prompts and reflective questions help students deepen their conceptual understanding and artistic vision.

- Tiered Technical Development:

- Students explore different ways to visualize narrative within an image, starting with traditional approaches. They first analyze how a single image can capture multiple events happening simultaneously, inspired by approaches like temple mural paintings where the viewer roves through the composition without a fixed perspective.

- At the next level, students experiment with sequential storytelling formats, such as comic strips or storyboards, to understand how time and narrative progression can be visually structured.

- Finally, students integrate various visual storytelling techniques, merging static and dynamic elements to create layered narratives that engage the viewer on multiple levels.

- This scaffolding process is supported by visual examples, guided activities, and discussions on narrative techniques across different artistic traditions.

- Progressive Conceptual Checkpoints:

- At key points in the project (e.g., after initial research, draft sketches, and mid-project reflections), students submit work-in-progress updates.

- Each checkpoint includes peer, teacher, and community member feedback, enhancing the collaborative and reflective aspects of the project and allowing learners to make iterative improvements.

Social Constructivist Approach

Collaboration is integral to this learning experience, supporting social constructivism by promoting dialogue and the sharing of diverse perspectives. This process fosters schema development, as students build upon their existing understanding of their community through exposure to new ideas and feedback. The class will incorporate the following social constructivist strategies:

- Peer Collaboration: Stretch & Explore (SHoM) and Social Interaction (Constructivist)

- Students participate in small groups to share ideas, offer critiques, and discuss different approaches to their projects.

- Peer groups meet weekly in video sessions to review progress and provide constructive feedback, fostering a sense of community.

- Community Interaction: Reflect (SHoM) and Situated Learning (Constructivist)

- Students engage with community members through virtual interviews or online forums to gain diverse perspectives on their chosen themes. This interaction allows students to reflect on their learning and artistic process, aligning with both the Reflect habit and situated learning by grounding their projects in authentic community experiences.

- This real-world interaction enriches their understanding of the subject matter and provides authentic context for their artwork.

Differentiation Strategies

Recognizing the diverse needs of learners, the instructional designer will:

- Offer Multiple Formats for Learning:

- Provide text-based instructions, video tutorials, visual examples, and access to the audio files in the “community seed bank” to accommodate various learning styles.

- Adjust Complexity Based on Skill Level:

- Advanced students may be encouraged to experiment with more complex techniques or multimedia projects, while beginners receive simplified exercises to build foundational skills.

- Provide Choice:

- Students choose their project themes and artistic mediums, fostering intrinsic motivation by aligning the activity with their personal interests and strengths.

- Implement Feedback Tiers:

- Facilitate a feedback system with peer, teacher, and community input to guide continuous improvement.

- Tailor the depth and complexity of feedback to match each student’s development level, ensuring supportive scaffolding at every stage.

Summary

This constructivist activity emphasizes active learning, where students construct their knowledge by exploring and engaging with real-world content. The Studio Habits of Mind are essential for structuring and deepening artistic exploration, aligning with constructivist principles such as inquiry, reflection, and social learning. This dual emphasis highlights how artistic habits can reinforce active engagement and collaborative knowledge construction within a constructivist learning framework. By scaffolding both artistic and research-based skills, and fostering interaction with peers and community members, students develop a collaborative and iterative learning process that enhances their understanding of both their art and their community.

Project Zero. (2003). Studio thinking: The real benefits of visual arts education. Retrieved from https://pz.harvard.edu/resources/eight-habits-of-mind